18th Century English Poetry: The Poetic Voice

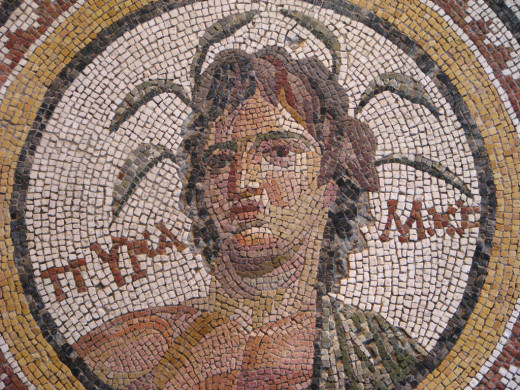

“The beauty of the [literary] body depends on the way in which the limbs are joined together, each one when severed from the others having nothing remarkable about it, but the whole together forming a perfect unity.” –Longinus, “On Sublimity”

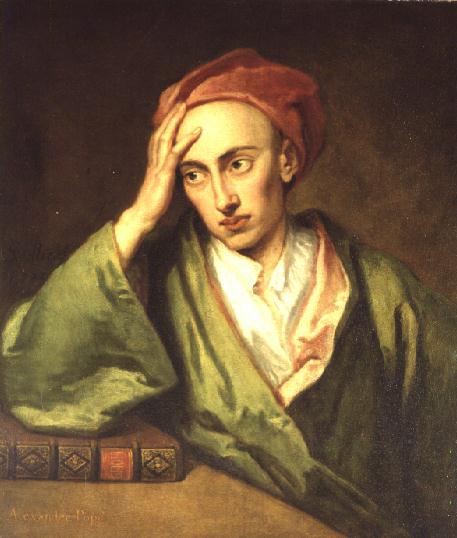

The Augustan era of 18th Century English literature is marked by an emphasis on decorum, satire, and a wider circle public readership. While literary forms such as diaries, letters, and the novel emerged and highlighted the prominence of individualism and private life, the poem was still the most prestigious form of writing (The emergence of new literary themes and modes, 2014). Furthermore, literary rates increased and by 1800, 60-70 percent of adult men could read, versus 25 percent in 1600, which had major implications on the nature of poetical matter and expression (Conditions of literary production, 2014). Ultimately, the nature of 18th century English language in poetry is marked by elevation and innovation, wittiness and pomposity, strict metrical structures, and a voice which intended to mimic the voice of kings, nobles, and courtiers. The English poets Alexander Pope, Johnathon Swift, and Andrew Marvell exemplify the high diction poetic voice of the Augustan era.

New-Historical Approach

If I were to analyze Alexander Pope’s “An Essay on Criticism,” Johnathon Swift’s “The Lady’s Dressing Room,” and Andrew Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress,” I would begin with historical research of the 18th century, which was characterized by the end of Renaissance humanism and the start of the Enlightenment. Even though most sciences began rejecting many traditions, poets still embraced the elegant rules of poetics set forth by their ancient, classic, and medieval predecessors Aristotle, Longinus, Horace, Geoffrey of Vinsauf, Pierre de Ronsard, Giacopo Mazzoni, and Sir Philip Sidney. Ultimately, prior to the Romantic era of English literature, the poetic voice was always highlighted with high or elevated diction. Furthermore, since the circles of public readership greatly increased during the 18th century, the publishing and consumption of literature became increasingly social. Thus, poets such as Pope, Swift, and Marvell began writing poetry not so much for self-reflection, but for an audience of readers.

Pope's Audience on Grub Street

Pope’s audience in “An Essay on Criticism” was in fact his enemy, the Grub Street poets. The 18th century marked the first time during which a large number of professional authors could earn a living. Many of these authors were crude and unrefined at the craft of verse, lacking the skills to write with proper diction and elegant figures of speech. This lower class of writers eventually were dubbed the label, Grub Street Poets, whom only worked on a piece by piece basis, and aimed their verse towards making a profit rather than embracing the pure essence of poetry, which Pope describes in lines 297-300, “True wit is Nature to advantage dressed,/What oft was thought, but ne’er so well expressed;/Something whose truth conceived at sight we find,/That gives us back the image of our mind” (Ferguson et al., pg.541). Understanding Pope’s audience sets his “An Essay on Criticism” on a historical stage, which ultimately accentuates the 18th century’s ideal poetical voice and juxtaposes it to the low diction and figures of speech used by the lower class of poets.

Swift's Juvenile Satire

Swift’s audience in “The Lady’s Dressing Room” is less specific than Pope. Even so, it can be argued Swift’s poem was intended for society as a whole: to satirize vanity in women and men’s unrealistic expectations of women. Swift’s poetical voice manifests an edgy wittiness unseen in previous ages of literature. His humorously vulgar content is concealed by a mask of high verse and elevated diction: “The stockings why should I expose,/Stained with the marks of stinking toes;/Or greasy coifs and pinners reeking,/Which Celia slept a week in?” (Ferguson et al., pg. 531). While the ultimate effect stirs an air of pomposity in Swift’s verse, his voice nevertheless exemplifies the art of rhetoric in poetical verse and the 18th century English voice. Understanding Swift’s poetical place in 18th century English society it very important to understand the nature of the English language during that time; clearly the language of poetry was increasingly becoming publicized and outspoken.

Marvell and Individualism

Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress” emphasizes the increasing importance of individualism in literature because it is essentially a personal poem. He hints at this in lines 6-7, “I by the tide/Of Humber would complain,” which is an allusion to the Humber River that flows through Marvell’s native town of Hull (Ferguson et al., pg. 435). Thus, in order to fully understand the language of Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress,” a considerable amount of biographical research would be needed to understand his speaker’s desperate lust for his subject.

Notes

[1] Thick multi-syllable words with more abstract definitions; as opposed to Saxonate words, which are single-syllable words with more concrete, practical, or corporeal definitions

[2] Standard English syntax is subject-verb-object. Inversion syntax is object-subject-verb or object-verb-subject

[3] Robert Burns was a major Scottish poet during the 18th century who was notorious for altering and abandoning traditional English grammar to evoke the Scottish dialect. He emphasized Saxonate words, and embraced basic syntax arrangements and vernacular spelling.

From New-Historics to Linguistics

Beyond historical research, it is natural for us examine the linguistics of Pope’s “An Essay on Criticism,” Swift’s “The Lady’s Dressing Room,” and Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress” to increase our understanding of the nature of the English language in poetry during the 18th century. As mentioned above, the linguistics of the English language in the 18th century poems is characterized by elevated diction. Essentially, high diction entails an emphasis on Latinate words [1], altered or unusual syntax [2], strict meter and rhyming structure, or blank verse, and traditional English spelling and pronunciation. Changes in traditional language were used only for stylistic effects, and never stemmed from sheer pomposity or ignorance [3]. Ultimately, this elevated diction was, in the words of Geoffrey of Vinsauf, to ensure that:

“Words do not enter as dry things, but let their meaning confer a juicy savor upon them, and let them arrive succulent and rare. Let them say nothing in a childish way; see that they have dignity but not pomposity, lest what should be honorable becomes onerous” (Cain et al., pg. 240).

Diction: Latinate Word Choice

While analyzing 18th century poems, it is important to read with a keen focus on diction; look for an emphasis on Latinate words, such as in Pope’s “An Essay on Criticism” in lines 201-“202: “causes…conspire/judgment…misguide,” Swift’s “The Lady’s Dressing Room” in lines 10-12, “inventory/appeared/besmeared,” and Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress” in lines 25-27, “beauty/marble/echoing” (Ferguson et al., pgs. 435, 530, & 539). Latinate words create more abstract visual representations in poetry. Furthermore, according to literary critic H. Coombes, this effect of abstraction in 18th century poetry functions to show a lack of emotional investment to their poetical content and subject (Siferd, 1998). Thus, the use of Latinate words over Saxonate words is consistent with the emotional detached, logocentric philosophies of the Age of Enlightenment.

Notes

[1] In Greek, lexis literally translates as “speech”; the word is variously translated as “language,” “word choice,” “expression,” and “style” (Cain et al., pg. 120).

Unusual Syntax

Analyzing the linguistics of the nature of the poetical voice in 18th century England requires further focus on the syntax, or grammatical arrangement on words in each sentence. Consistent with Latinate vocabulary and word choices poets used during 18th century English poetry, the syntax of sentences normally manifested in altered or unusual forms, opposed to the basic syntax: subject-verb-object. By rearranging sentences, poets could deviate from common usage of words to make language seem more elevated. For instance, this effect is accomplished in Pope’s “An Essay on Criticism” in lines 558-559, “All seems infected by that the infected spy,/As all looks yellow to the jaundiced eye,” Swift’s “The Lady’s Dressing Room” in line 47, “No object Strephon’s eye escapes,” and Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress” in lines 6-7, “I by the tide/Of Humber would complain” (Ferguson et al., pgs. 435, 531, & 547). Aristotle in his poetics explains that “people feel the same in regard to lexis [1] as they do in regard to strangers compared with citizens. As a result, one should make the language unfamiliar, for people are admirers of what is far off, and what is marvelous and sweet” (Cain et al., pg. 121). Thus, along with choosing Latinate words over simpler Saxonate words, altering traditional syntax can also defamiliarize the English language into something high and elegant: a major aim of 18th century poets as exemplified above by Pope, Swift, and Marvell.

Be a Critical Reader

While analyzing 18th century English poetry, it is imperative to focus on the function of decorum in any given poem because in high styled poems, poets will appeal to all varieties of amplifications and digressions; they will unleash everything in their literary arsenal to create elegant, natural, and pure poetry, to ultimately mimic the voices of kings, nobles, and courtiers.

Combining New Historic and Linguistic Methods of Analysis

Historical and linguistic analyses provide us a solid foundation of research and understanding, but nevertheless alone they leave us incomplete in our ultimate examination of the nature of the English language in 18th century poetry. To complete this analysis of the 18th century poetic voice we must pursue a poetic analysis, highlighting instances of amplification and curtailing, the purpose and function of such figures of speech, and their ultimate effect. Consistent with the high diction of 18th century poets, so too did 18th century poets embraced elevated stylistics of figurative language such as alliteration, consonance, metaphor, and simile among many other literary devices and conventions. In fact, 18th century poets referred to decorum as an actual convention of writing, which called for the style of a work to “match” or be consistent with all its other aspects (Murfin R., Ray S., pg. 463).

This is arguably the most important figurative convention of poetry during the 18th century because it highlights the importance of the balance and unity between words and concepts. We see this poetical embellishment active in Pope’s “An Essay on Criticism” in lines 22-24, “Time’s winged chariots hurrying near;/And yonder all before us lie/Deserts of vast eternity,” Swift’s “The Lady’s Dressing Room” in lines 141-144, “He soon would like to think like me,/ and bless his ravished eyes to see/Such order from confusion sprung,/Such gaudy tulips raised from dung,” and Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress” in lines 33-34, “Now therefore, while youthful hue/Sits on the skin like morning dew” (Ferguson et al., pgs. 436, 533, & 547). Ultimately, these excerpts function as remarkable links in the unity and completeness of each poem; in their exclusions these poems would suffer a lack of figurative ingenuity and technical genius, and perhaps never reach the state of sublimity and age-old significance they known for today in the literary canon and English poetry.

Summary and Concluding Thoughts

Overall, to understand completely the nature of the English language in 18th century poetry, we must view the era under several different microscopes- historical, linguistic, and poetic- because each lens tells a different story. Historical contexts help us establish a solid foundation for inquire, and also give us leads on new perspectives or interpretations on authors, publishers, manuscripts, and intended audiences. Linguistic research helps us identify the conceptual thoughts of the poets and their stance on the evolution of the English language such as appealing to tradition or experimentation in forms, content, or stylistics. Lastly, poetic analyses help us form meaning, and identify significance in poems. Together, by examining the raw materials, gathering the blueprints for analysis from outside resources, and finding tools of theory and criticism to effectively pick apart a poetical text, we can dig into it with all our riggings in hand and attempt to extract a few excerpts of gold.

Find these on Amazon

References

Cain, W., Finke L., Johnson B., Leitch V., McGowan J., & Williams J.J.(2001) The norton anthology: Theory and criticism (1st ed.) New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Ferguson, M., Salter, M. J., & Stallworthy, J. (Eds.). (2005). The Norton anthology of poetry (5th ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Murfin R., Ray S. (2003). The bedford glossary of critical and literary terms. Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Period Introduction Overviews (2014) The restoration and 18th century: The emergence of new literary themes and modes; Conditions of literary production. Norton & Company, Inc. Retrieved from http://wwnorton.com/college/english/nael9/section/volC/studyplan.aspx

Siferd, S. (1998). comparisons of swift's "the lady’s dressing room" and pope's "rape of the lock". Retrieved from http://homepages.wmich.edu/~cooneys/tchg/640/papers/prot/Siferd.eval.html